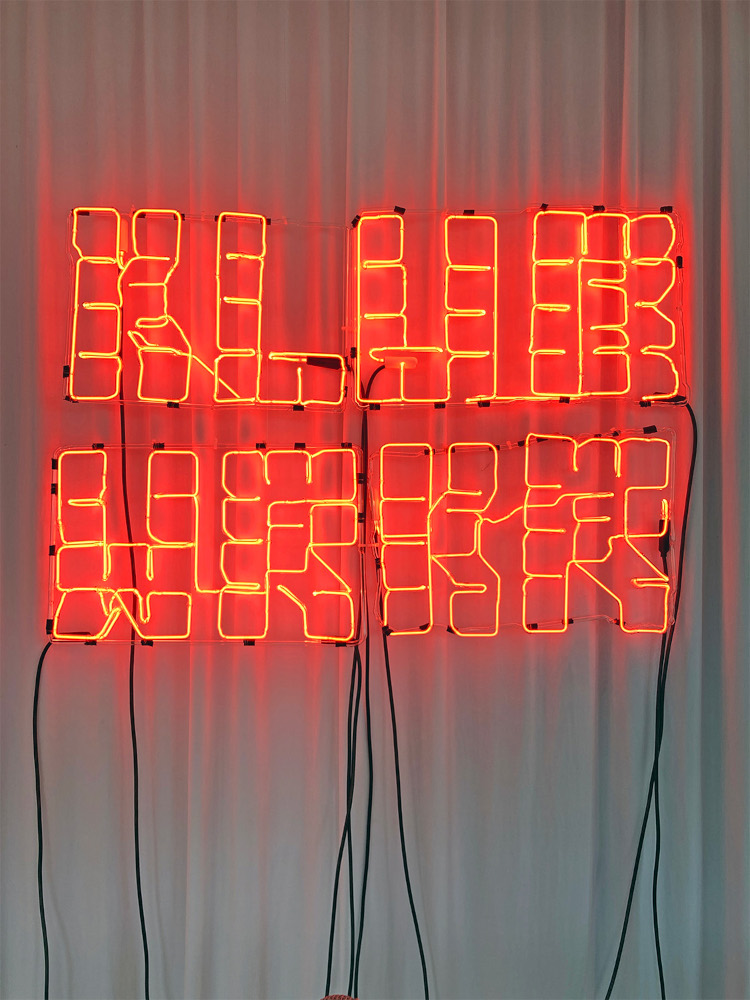

Friend of the Program, after Rodchenko

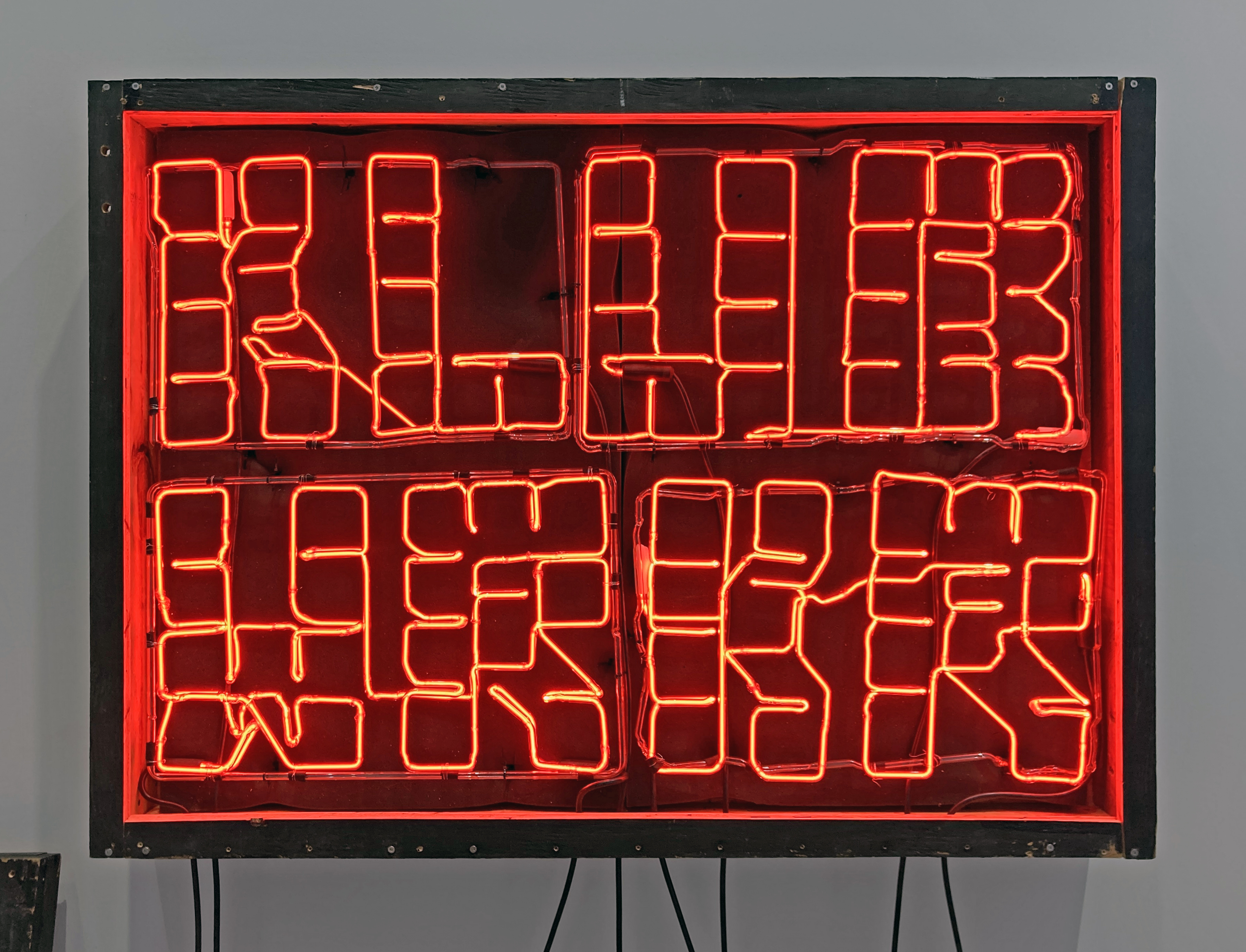

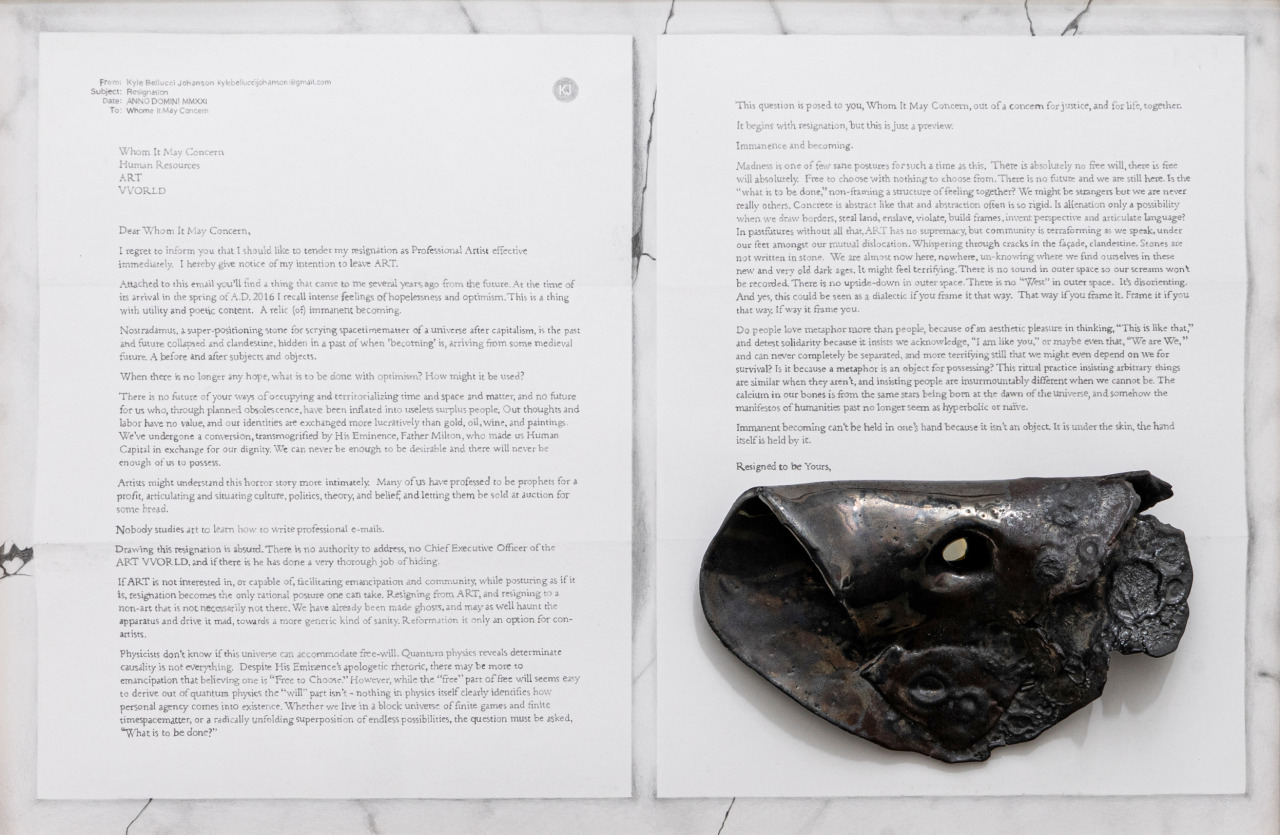

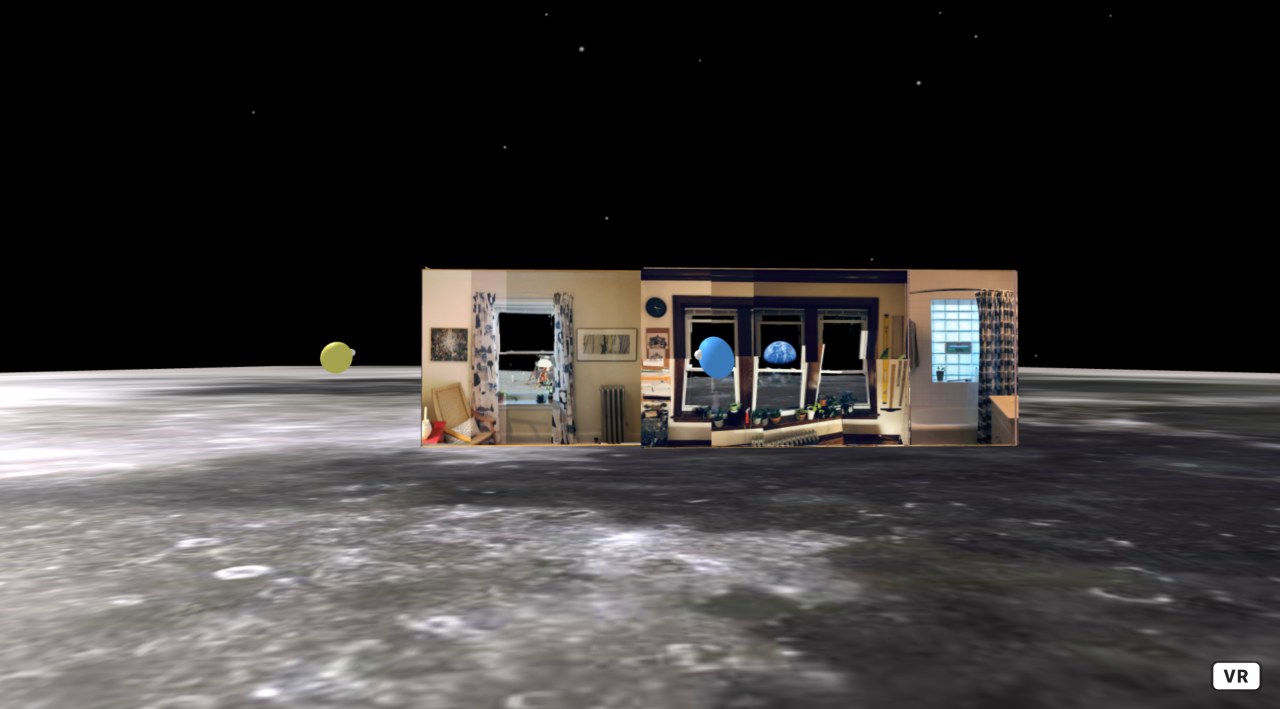

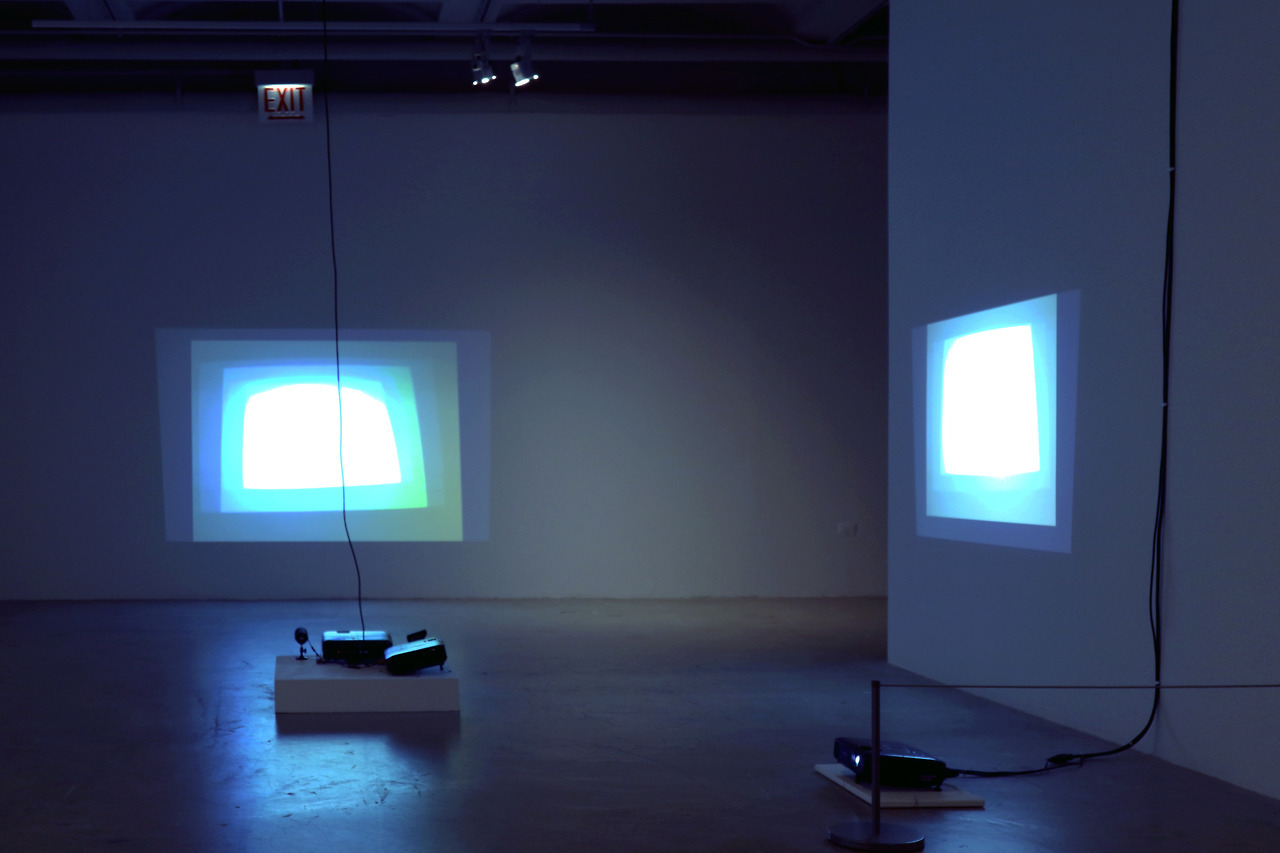

2023Musical composition for duet, two-channel video, video performance object, stage curtains, neon

Dimensions variable

This work was exhibited as part of:

No Necessary Correspondence

Whitney Independent Study Program

100 Lafayette Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY, 10003

May 17—28

Tuesday—Sunday, 12-6pm

This work was made possible through the participation of the following interlocuters:

Hal Foster, Tim Tsang, Andrea Fraser, B Neimeth, Alfredo Jaar, Andre Keichian, Matthew Lax, Mark Nash, Nyeema Morgan, Emma Roberts, Mary Kelly, Mary Coyne, Coco Fusco, Joestine Con-ui, Silvia Federici, Liang Luscombe, Nora Alter, Carmen Amengual, Sharon Hayes, Haynes Riley, David Harvey, Chloe Munkenbeck, Soyoung Yoon, Ali Aschman, Gregg Bordowitz, Kioto Aoki, Adam Feldmeth, Will Lee, Kelly Xi.

Thank you, Ron.

Friend of the Program catalog essay

The first essay written in France was also a love letter for a friend who had died.1

What a comfort that Montaigne didn’t choose one form over the other.

I came to New York to leave Chicago. I lost a friend there named Gregory Bae, an artist’s artist.

I didn’t like what the city was like without him.

That doesn’t really say it right but hopefully you can understand how I felt. I didn’t like facing daily social life without him. I hadn’t realized how much I relied on the community between us.

I arrived in early September, one of twenty-two participants of the heavily mythologized Independent Study Program, in its final year at 100 Lafayette under the direction of Ron Clark. Within a couple of weeks two aspects of the program had come into focus. First, this thing is theater; a didactic play in a state of constant reproduction that has been sustained more or less this way since the early ’80s, complete with a stage manager/director/narrator and a cast who are ushered on and off stage to perform biweekly seminars. Second, a central organizing framework of the ISP are the friends of the program. These committed social relations spanning decades sustain this historical intervention, at times beyond the lifespans of its comrades.

Being an artist can often feel clumsy, stumbling around in the dark so to speak, hoping to bump into an idea or co-conspirator to navigate that space of unknowing with.

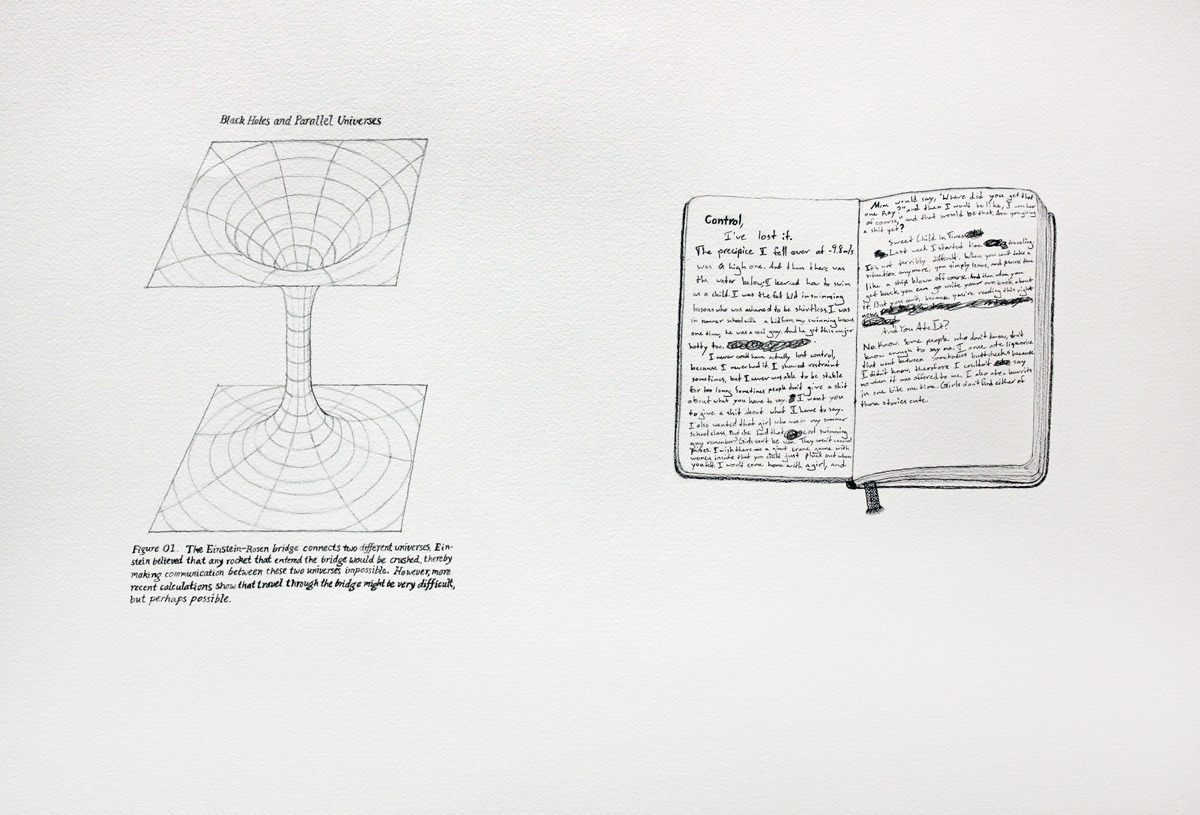

Greg made a show in the dining room of my apartment during (at his request) the coldest, darkest month of 2019. Black Hole of Love ⁄ 사랑의블랙홀 was a constellation of poetic experiments attempting to freeze time. Greg magnetized an atomic clock’s second hand, placing it in a relentless and futile effort to move forward, a kind of tiny quiet purgatory. The clock’s glass face had been meticulously etched and painted to resemble an array of rain droplets, mimicking in great detail the ones Greg noticed on the porthole window of the plane that would eventually take him back to the U.S. while it sat on the tarmac of the Seoul airport. Greg was losing a love at the time, and leaving a place of deep significance. He referred to this show as a response to losing love and indulging in that loss, saying, “a cosmic indifferent force will not yield to anyone’s heart. The desire to stop time is, nevertheless, as egotistical as it is romantic.”

The only worthwhile reason to make art, or to do anything for that matter, is to make friends.

I suspect there might be something worth noticing between the effort to freeze time and the effort of cultural reproduction. Maybe it’s something about revolution. Perhaps it has to do with a notion of community or belonging. In either case there is loss. We’ve certainly been grieving.

Karaoke is a form of theater that most everyone has experienced in one form or another. Performed for friends and yet-to-be friends alike, it can be done in earnest or in biting irony. It’s a chance to participate in cultural reproduction and criticality. It is also usually fun. Just before the pandemic, Greg and his partner Ali came over to my flat in Chicago. We shared a few drinks late into the night which led to a spontaneous series of YouTube karaoke duets.

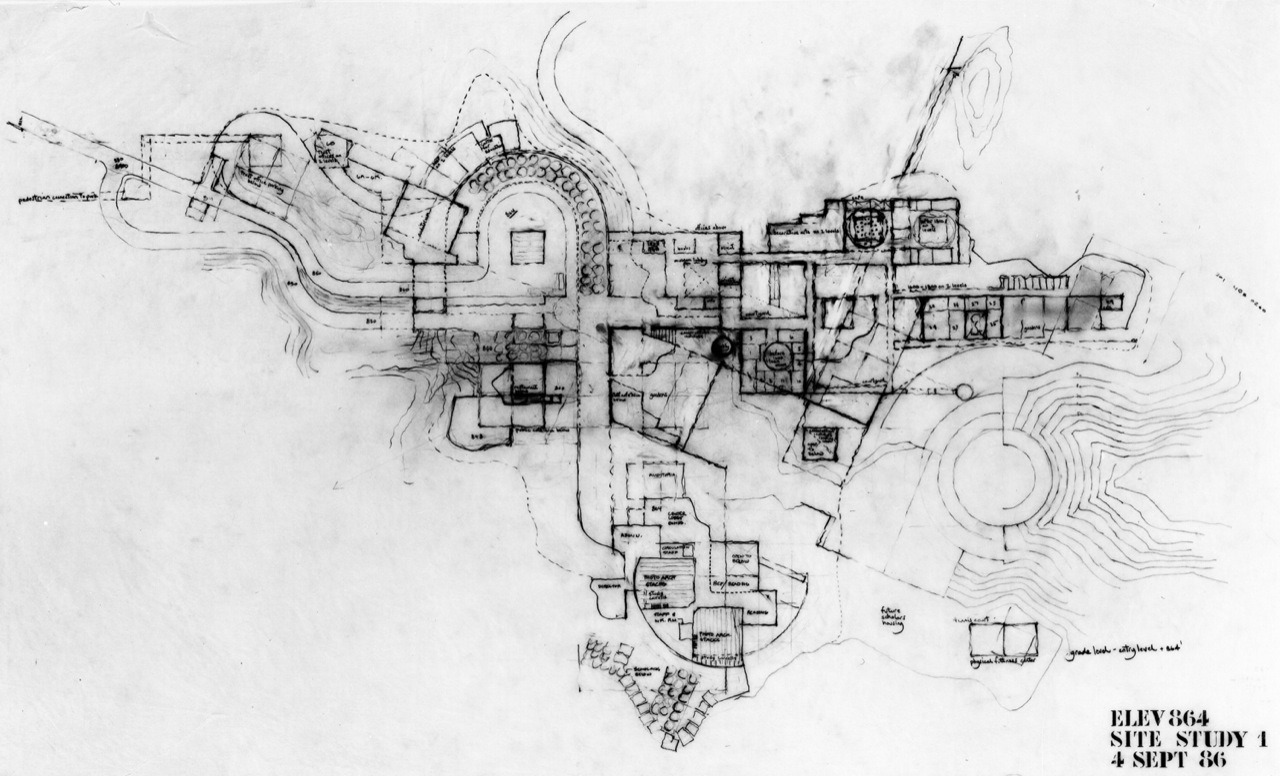

I often think about Alexander Rodchenko’s Workers' Club, that he designed and built for the 1925 International Exhibition of Decorative Arts and Modern Industry in Paris, just after Lenin had died in the fever of paranoia and optimism between two world wars. Designed as an optimal space for workers to engage in self-education and cultural leisure activities including chess, I wonder what activities Rodchenko would incorporate had he designed it a century later. Perhaps he would make a dialectical karaoke machine where the chess table had been, a platform for cultural reproduction and critique, where participants could perform the words of other cultural workers set against popular melodies, comrades antagonizing hegemony. I suspect they’d all be duets if not full choral situations.

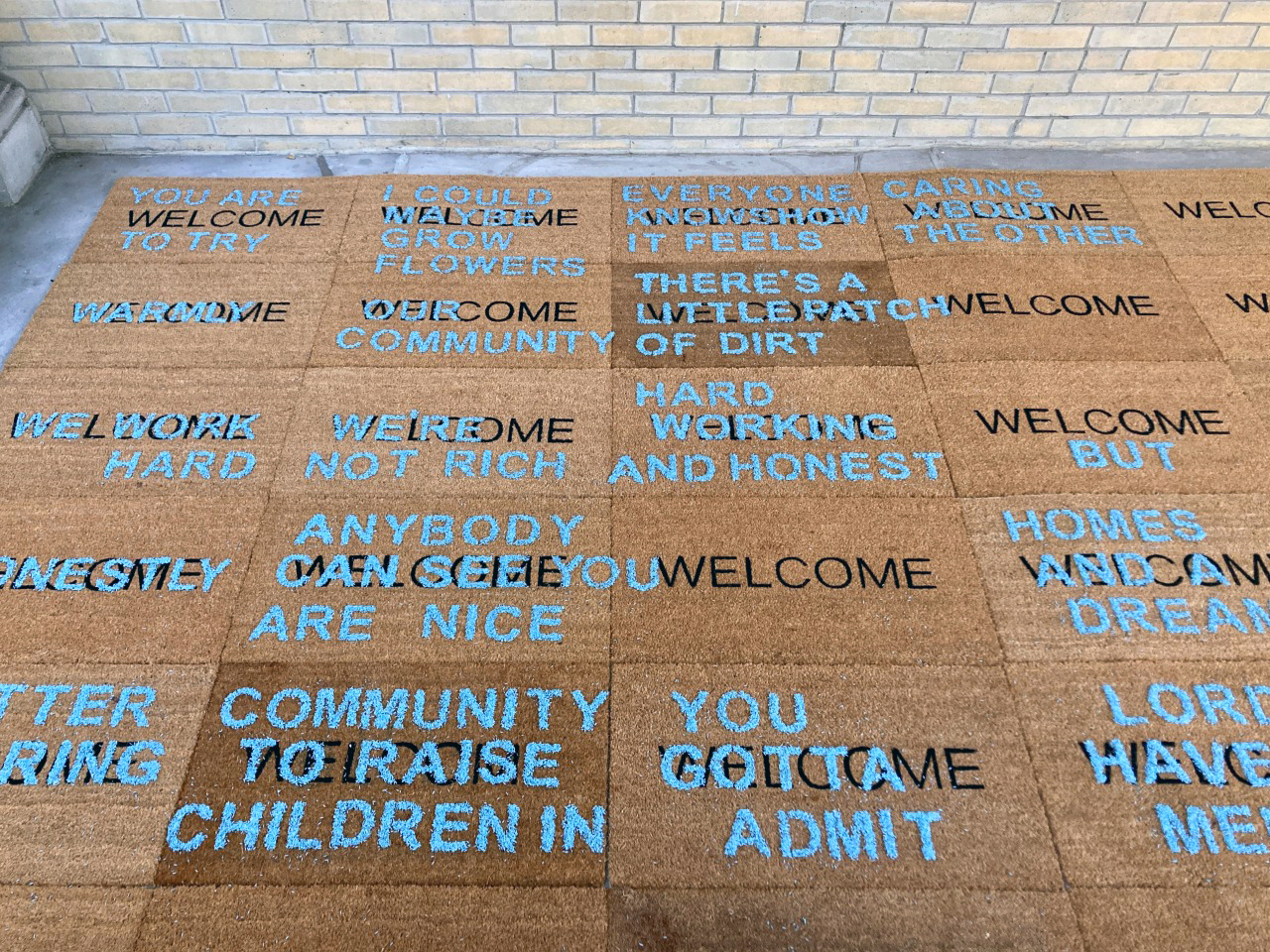

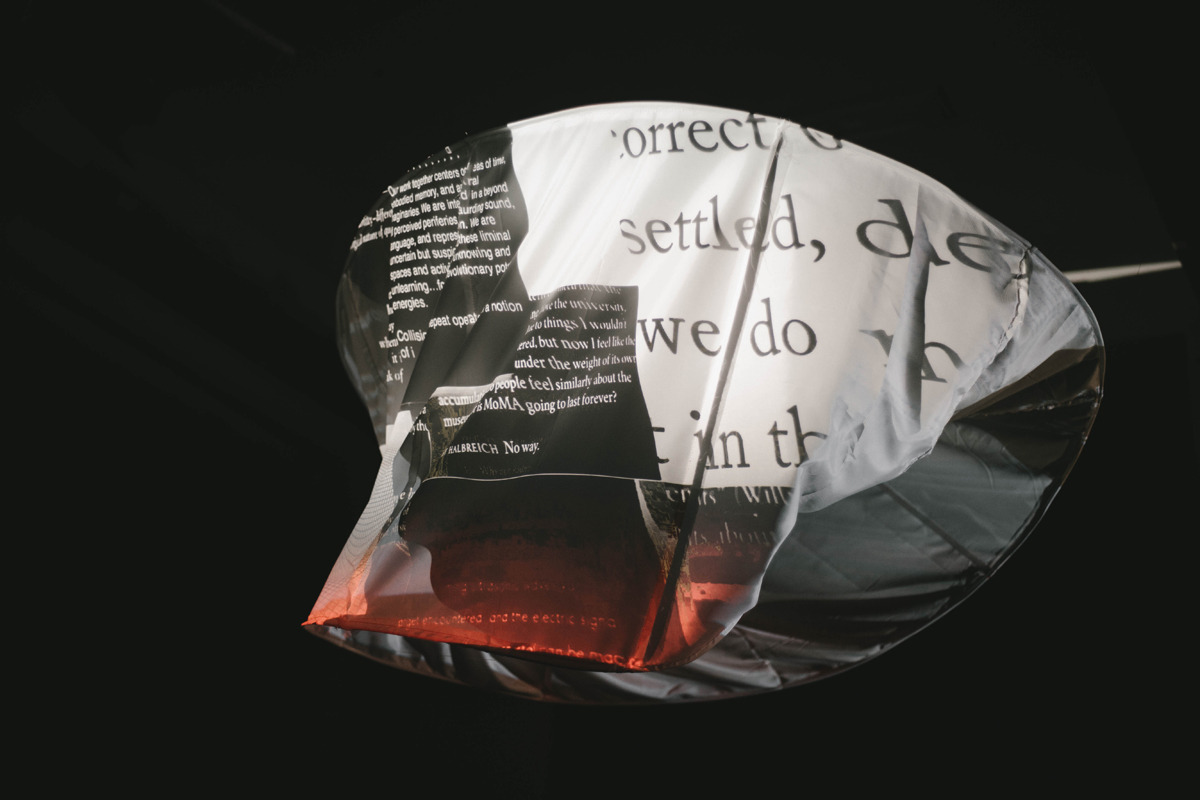

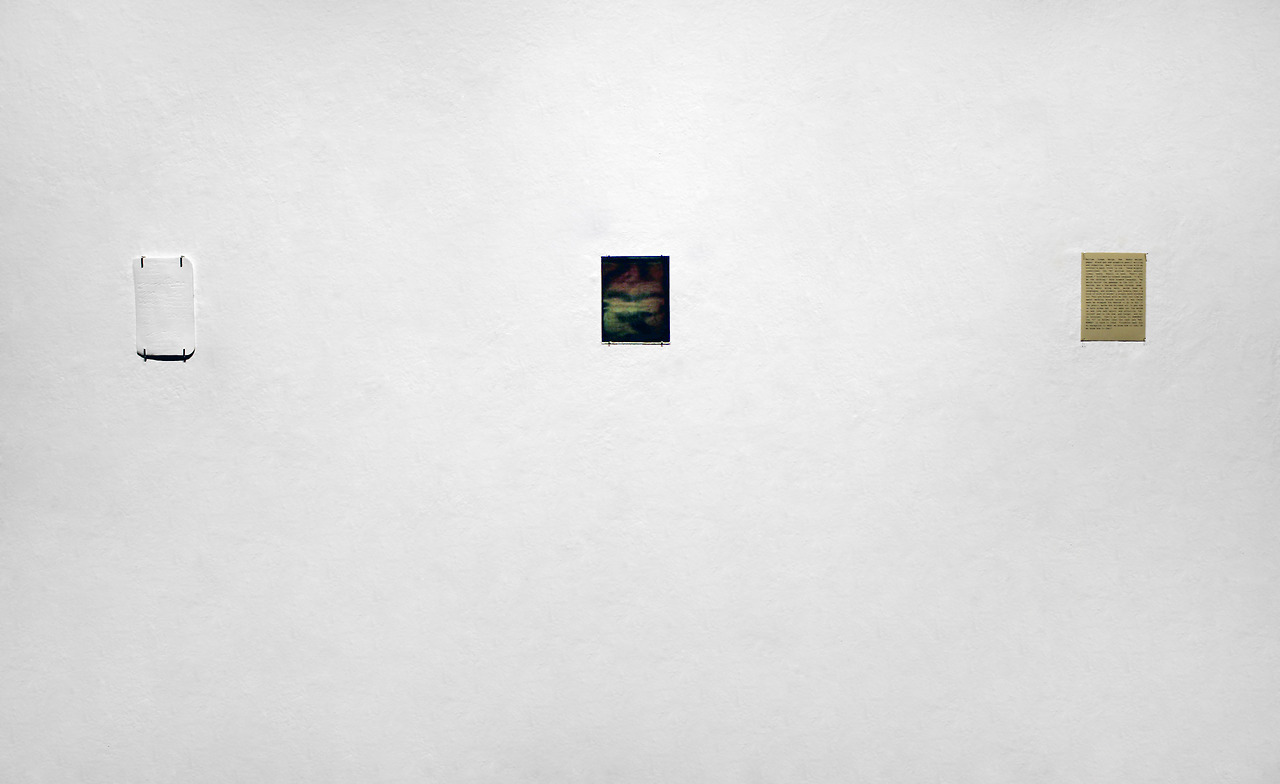

For the past several months I’ve asked our faculty, several generations of critical cultural workers and friends of the program, to reflect on the politics of friendship in relation to their work at the Independent Study Program. Concurrently I’ve asked my own friends, with whom I have established mutual commitments, to identify their favorite political karaoke songs. They have interpreted ‘political’ and ‘karaoke’ on their own terms. I’ve overlayed the faculty’s transcribed reflections as lyrics to these songs, played through a two-channel karaoke machine designed in the style of Rodchenko’s chess table, in a performance-architecture remodeling the workers club into KLUB WRKR.

The intimacy of friendship lies in the sensation of recognizing oneself in the eyes of another.

Friendship for the deceased thus carries this philía to the limit of its possibility. But at the same time, it uncovers the ultimate spring of this possibility: I could not love friendship without projecting its impetus towards the horizon of this death. The horizon is the limit and the absence of limit, the loss of the horizon on the horizon, the ahorizontality of the horizon, the limit as absence of limit. I could not love friendship without engaging myself, without feeling myself in advance engaged to love the other beyond death.2

Our friends are often made heroes when they die. I suspect this is some sort of attempt to cope with their absence or to honor them. We fear they will be forgotten so we make them monuments. This happens all-too-often when these friends are cultural workers, and in some cases it happens before they’ve died. Institutions clamor to preserve their so-called “authenticity,” as if they had never been dynamic contradictory beings. Brecht’s words through the mouth of Galileo have particular utility here, in a way I find fitting as Brecht himself has been made a monument. “Unhappy is the land that needs heroes,”3 Galileo reminds his former student.

Monuments can’t speak and they certainly can’t sing. We can. We can see ourselves in an other’s words as we perform them, we can take them up or reject them, offering inflection and interpretation that may have been absent in previous renditions, and we can offer something far more interesting than kindness as we lend our criticality and participation.

- Michel de Montaigne, “That Men by Various Ways Arrive at the Same End” in Essais (Simon Millanges, Jean Richer, 1580), 1.

- Jacques Derrida, “Oligarchies: Naming, Enumerating, Counting” in The Politics of Friendship (Verso, 1993), 12.

- Bertolt Brecht, “Scene 12” in Life of Galileo (Grove Press, 1966), 115.